The World as a Circle: How Monsters Are Made

Exploring the narrative of crime and influence.

Victory Atet

Victory Atet is a Nigerian writer, editor, and creative strategist whose work explores the intersections of faith, identity, culture, and the human condition. She is the founder of Faith, Art, and Culture (FAC) — a personal and public space dedicated to reflective writing and thoughtful engagement. Rooted in poetry, essays, and editorial work, her writing is shaped by emotional depth, thematic clarity, and a commitment to nuance. With experience in creative support and project coordination, Victory collaborates with individuals and platforms to refine ideas, shape content, and drive intentional communication. She brings an analytical mindset, strong research skills, and a cross-disciplinary approach to every project, believing in the power of language to influence, clarify, and transform.

The World as a Circle: How Monsters Are Made

Author: Victory Atet

Date: 2025-11-07

tags: [Society, Nigeria, Crime, Religion, Psychology, Culture, Family, Violence, Essay]

Subheadline

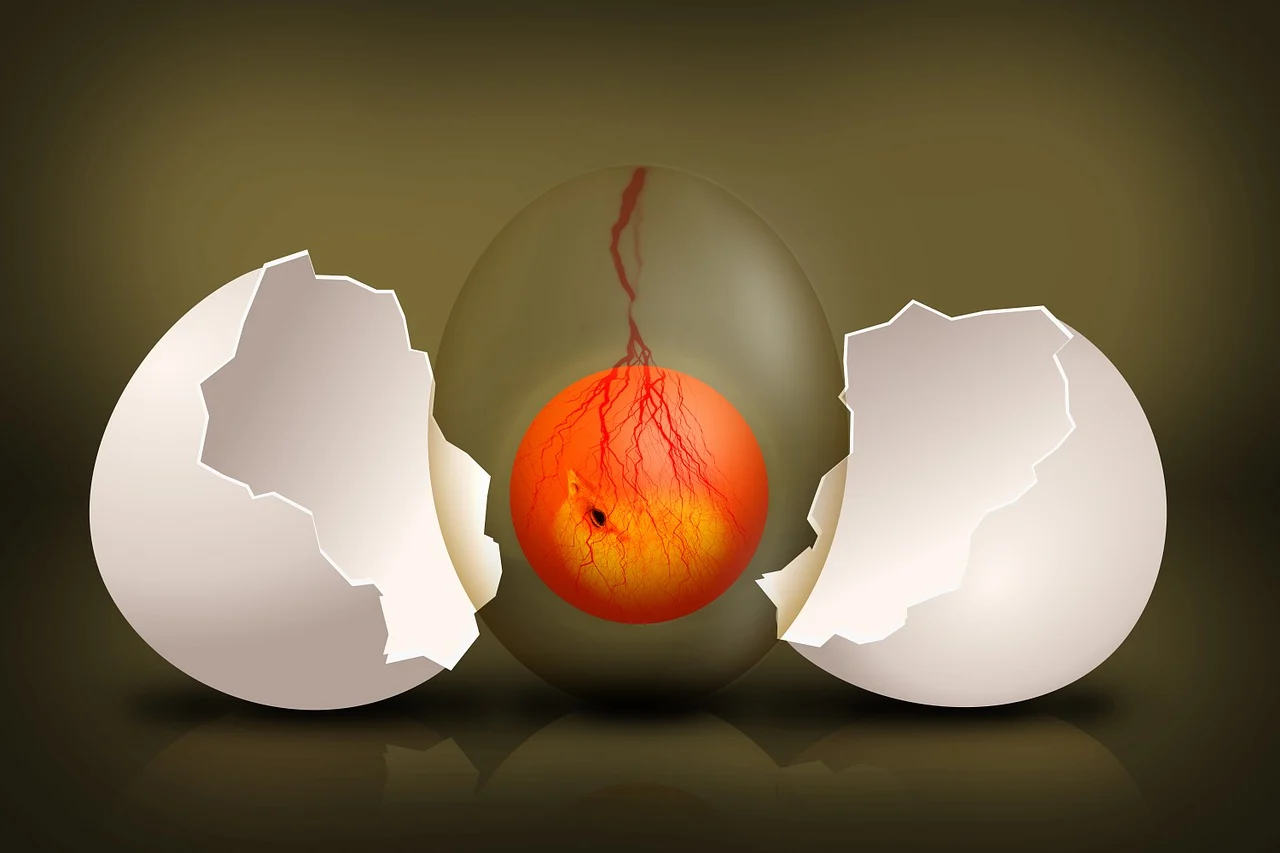

When homes neglect, societies fail, and religions mislead, monsters are born — and the world receives back what it has created.

Abstract

No one is born a criminal. Behind every act of violence or fraud lies a circle of influences — the home, society, and religion — that shaped the individual long before the crime.

In Nigeria today, rising kidnappings, banditry, and fraud are not accidents of fate but the predictable result of long-standing failures. Families marked by neglect or abuse raise children without stability. Societies riddled with poverty and glamorized corruption reward desperation and shortcuts. Religions that should restrain violence sometimes sanctify it, whether through extremism or the commercialization of faith.

Drawing on criminology theories and real-world evidence, this article argues that monsters are made, not born. Nigeria’s current crisis is the echo of yesterday’s broken homes, corrupt systems, and compromised pulpits. Unless these circles are reformed, the cycle will continue, and the monsters of today will become the architects of tomorrow’s broken world.

Introduction

Fyodor Dostoevsky once wrote, “People are either circumstances or they create circumstances.” In Nigeria today, that observation is not just a philosophical musing but a lived reality.

Behind every crime statistic lies a broken life and a broken system. In 2024, the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) ranked Nigeria among the most violence-stricken nations in the world, documenting more than 50,000 conflict-related deaths. SBM Intelligence reported that kidnapping for ransom had evolved into a full-fledged economy, feeding on fear and despair. Even the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), before retracting its contested data, acknowledged a frightening rise in abductions and fatalities. Independent accounts by Reuters and the Associated Press painted the same picture: waves of mass kidnappings, including the abduction of hundreds of children in Kaduna State in 2024.

These are not random tragedies. They are symptoms of deeper, older wounds. No one is born a criminal. Every thief, kidnapper, or extremist once learned to walk and speak under someone’s roof, in some community, and often under the shadow of religion. Monsters are not born in isolation; they are made in circles — the family, the society, and the faith traditions that surround us.

The Family: Where the Circle Begins

The family is the first classroom of life. A child learns not by listening to sermons but by watching how a father speaks when angry, how a mother responds under pressure, how siblings resolve conflict. When violence, deceit, or indifference dominate this early stage, they set the rhythm for adulthood.

As Albert Bandura argued in his Social Learning Theory, children are mirrors of what they see. But the health of the home matters as much as its culture. A peaceful home nurtures resilience; a broken one poisons the soul. Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) shows that children exposed to neglect, domestic violence, or parental substance abuse are far more likely to engage in delinquency as adults. Cathy Widom’s landmark “Cycle of Violence” research revealed that childhood abuse often echoes forward, shaping futures of crime and imprisonment.

The evidence is not just academic. Aileen Wuornos, often called America’s first female serial killer, endured abandonment and abuse so severe it became a textbook example of how monsters are made. In Nigeria, similar patterns echo in juvenile correctional centers, where the majority of young offenders come from homes marred by divorce, neglect, or violence. The silence of an unhealthy home often shouts the loudest in the making of tomorrow’s criminals.

Society: The Seed Takes Root

If the family plants the seed, society waters it. For children raised in ghettos, crime is not theory but survival. Streets where hunger prowls louder than the police teach their own lessons: be cunning, be tough, or be consumed. Criminologists call this social disorganization — when neighborhoods cannot maintain informal social controls, gangs and criminal subcultures fill the vacuum. In Nigeria’s slums and rural conflict zones, this disorganization is visible in every kidnapping camp and gang-infested corner.

Hunger and poverty push many into desperate choices. The World Bank noted that the removal of fuel subsidies in 2023 sent inflation soaring and deepened food insecurity for millions of Nigerians. For parents unable to feed their families, theft, fraud, or banditry often became the only viable path. This mirrors Robert Merton’s Strain Theory, which explains how people resort to crime when legitimate routes to success are blocked.

Yet poverty is not the only trap. On their screens, young Nigerians see celebrities dripping in luxury cars, watches, and mansions, often financed by questionable means. Songs celebrating “Yahoo boys” glamorize internet fraud as though it were not crime but craft. As Al Jazeera reported in 2021, cyber-fraudsters have become folk heroes in some subcultures. Here, the lesson society teaches is chilling: integrity is optional, wealth is mandatory.

Religion: When Faith Turns Its Face

Religion should act as a compass, pointing individuals toward good. In practice, it has often done the opposite. The case of Boko Haram illustrates the danger. Its founder, Muhammad Yusuf, cloaked economic grievances in sacred language, convincing marginalized youths that violence was not only permissible but holy. Terrorism in this form is not just political; it is theological.

Even outside extremism, religion sometimes distorts morality in quieter ways. The rise of prosperity preaching has tied faith to wealth, convincing congregations that riches are proof of divine favor. When the miracles fail to arrive, shortcuts — fraud, corruption, or violence — step in as substitutes. Sociologist Mark Juergensmeyer calls this “sacred violence”: when the very institution meant to restrain evil becomes its justification. In Nigeria, this paradox is plain. Religion can save, but it can also sanctify the very monsters it should have stopped.

The Circle Returns

When the family neglects, society corrupts, and religion misleads, the circle is completed and monsters are made. But the circle does not end there. Those monsters grow up to become fathers, mothers, politicians, and preachers. They, in turn, shape the next generation’s families, societies, and religions.

The world is a circle, and circles always return. Today’s violence is yesterday’s seed; tomorrow’s despair is today’s harvest. If we keep planting neglect, corruption, and falsehood, the field will keep yielding monsters. To change the story, we must change the seed — nurturing homes with love, shaping societies with justice, and guiding faith back to truth. Only then will the circle return, not with monsters, but with men and women who heal what they once inherited.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Crime and Security Data, 2023.

- Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), Nigeria Annual Report, 2024.

- SBM Intelligence, The Economics of Kidnapping in Nigeria, 2024.

- Reuters, “Mass Abductions in Nigeria Signal Rising Insecurity,” March 2024.

- Associated Press, “Hundreds of Children Abducted in Nigeria’s Kaduna State,” March 2024.

- World Bank, Nigeria Development Update: Seizing the Opportunity, 2023.

- Al Jazeera, “Yahoo Boys and the Glamourization of Fraud in Nigeria,” 2021.

- Widom, Cathy. The Cycle of Violence: Child Abuse and Criminality, National Institute of Justice, 1989.

- Bandura, Albert. Social Learning Theory, 1977.

- Merton, Robert. “Social Structure and Anomie,” American Sociological Review, 1938.

- Juergensmeyer, Mark. Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence, 2000.

About Victory Atet

Victory Atet is a Nigerian writer, editor, and creative strategist whose work explores the intersections of faith, identity, culture, and the human condition. She is the founder of Faith, Art, and Culture (FAC) — a personal and public space dedicated to reflective writing and thoughtful engagement. Rooted in poetry, essays, and editorial work, her writing is shaped by emotional depth, thematic clarity, and a commitment to nuance. With experience in creative support and project coordination, Victory collaborates with individuals and platforms to refine ideas, shape content, and drive intentional communication. She brings an analytical mindset, strong research skills, and a cross-disciplinary approach to every project, believing in the power of language to influence, clarify, and transform.